The birth were astonishing for the rare bear, and

they captivated the world. The San Diego Zoo proudly announced the

arrival of the first panda cub born in the United States in a decade

on Aug. 21. Every move made by the mother, Bai Yun, and her unnamed

cub was noted by scientists, packaged by public relations experts,

dispatched to reporters and turned into headlines around the world:

"Bai Yun soothes the baby when it cries out!" "Bai

Yun sleeps for 64 minutes in official first nap after birth!"

The week before, triplets had been born at the Giant Panda

Breeding Research Center in China's Sichuan province. (One cub has

since died of a bladder disorder.) Twins arrived at the Beijing

zoo on Aug. 23, prompting the Xinhua News Agency to praise the "hero

mother."

You'll be hard pressed to find another species

that creates such fervor over the simple act of reproduction. Perhaps

it is because it's never simple for rare and endangered giant pandas

in captivity.

The pandas in zoos and breeding centers

have long had a reputation as notoriously difficult breeders. They

have been described as having "low sex drives," as being

"clumsy" lovers, or even frigid. "But if we are going

to use human emotions to describe the behavior of these bears, try

looking at the entire mating process through the captive pandas'

eyes.

Humans typically choose their mates; captive pandas

usually get few choices or none at all. While we can get as much

"practice" as we can manage or desire, they are limited

to the few days in spring when a female goes into heat. In addition,

we have some control over our privacy. Captivity pandas are often

closely watched, with every move scrutinized, every mating attempt

recorded.

"There are a lot of pieces in the puzzle, and

we have to figure out what is missing. What is it that we are not

providing in captivity?" says Rebecca Snyder, senior research

associate at zoo Atlanta, which expects its first panda pair to

arrive in Georgia from China this fall.

People are trying

yo breed giant pandas because they are so rare. The World Wildlife

Fund estimates that fewer than 1,000 remain in the wild, reduced

in large part due to disappearing habitat. According to the 1997

census, slightly over 100 are in captivity.

To increase

the panda's overall population and keep it healthy, scientists have

been using artificial insemination over the years with mixed results.

Other options being eyed or investigated include the use of fertility

drugs, cloning and even the drug Viagra.

But in the United

States, the focus has been primarily on natural breeding. Working

with the second largest panda breeding center in Chengdu, Snyder

has spent the last two and a half years going back and forth to

China to do behavioral research. She's particularly interested in

the relationship between panda mothers and their children.

The Atlanta team of researchers has been working with Chinese

scientists to allow captive cubs to stay with their mothers longer.

Perhaps they learn breeding or socialization skills by staying at

her side, she says. Often when baby animals are isolated

growing up, they become fearful of other animals as adults. It is

common for pups to be taken from their mothers around six months

after birth in china so that the mother is able to breed within

a year, she says.

What has become increasingly clear is

that pandas need to know each other before a successful mating can

occur, according to Lisa Stevens, associate curator of mammals

at the National Zoo in Washington, D.C.

When the zoo's

first pair arrived in 1972 as a diplomatic gift from China, the

advice was to keep the pandas apart as much as possible. when the

pandas did get together in the first few years, there was a lot

of aggression.

But the zoo started a regular routine of

allowing them in each other's enclosures. Stevens believes this

eventually led to the successful mating between the two pandas,

Hsing-Hsing and Ling-Ling, who eventually gave birth to five cubs,

though none survived.

The captive population, so far,

has not been self-sustaining. From 1963 to 1997, there have been

197 births in captivity, but only a third of those survive to adulthood(around

65% mortality). About 40% do not make it through the first 30 days.

Researchers are also taking cues from populations in the

wild, where pandas have no mating problems and rely on scent for

important information. From scent, they can identify another panda,

its sex and age. Wild male pandas have been observed to gather around

a female and compete for a chance to mate with her, Snyder says.

The dominant male may breed first and the other males may also try.

"There may be some kind of learning that is going

on-or they might need that competition to be stimulated. That's

something that cannot be replicated in captivity, "she says.

While most researchers agree that natural breeding is

best, artificial insemination remains important for gene diversity,

especially in such a small population.

Before the female

Ling-Ling died at the National zoo, her follicles were removed so

that, if the technology exists one day, scientists could create

a bear using Ling-Ling's genes. Hsing-Hsing's semen has been collected

several times and used in insemination attempts at different zoos

around the world.

But these high-tech tools raise another

dilemma, says Changquin Yu, an official with the World Wildlife

Fund's office in China. The growth in artificial insemination "will

make the captive giant panda more and more domesticated," he

says. "And how can the domesticated giant panda be reintroduced

to the wild?"

Smita Madan Paul, a freelance journalist

A rare three-cub

litter was born mid-August 1999 in southwest China's Sichuan province.

A baby panda's rear legs

and body are shown in this surveillance video at the San Diego zoo.

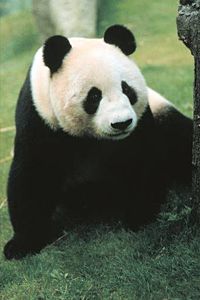

The panda

mother Bai Yun is viewed through a special camera.

A giant panda cub

born at the National zoo in 1987 died of liver failure four days

after birth.

Ling-Ling

gave birth to five cubs at the National zoo during her residence

there, but they all died of different causes.